In America, those who have lived here their whole lives may have never experienced what it's like to completely find themselves in a new land.

Most may find themselves in their normal day-to-day lives where they mostly deal with themselves, not the lives of others.

They may find themselves getting a glimpse into someone else's life, but no deep dive into who a person really is, or where they come from. For the people they’ve known their whole lives, it makes sense. They know who that is. But what about someone new to the country?

For international students at Marshall University, coming to America and embracing the culture and norms can be daunting, but they say it is a journey of wonder. From the differences and similarities between their homes, new and old, they all find something here they love.

Stepping on New Ground With Uneasy Footing

For Moeka Ueura, a Japanese woman studying English to teach it in America, there were many adjustments to be made when arriving here.

As the COVID-19 pandemic was spreading across the world, so was a negative look on Asians who were blamed for the start of the virus.

Ueura said that while wearing a mask she would be looked at with distaste, and some even shaking their head at her. Apart from these interactions, Ueura said that this was the closest to racism she had come across so far in the U.S.

“Racism? No. I can’t think of anything that happened to me. Everyone is generally so nice here,” said Ueura.

Ueura said she was told by her family she would face a lot of it when leaving for the U.S. but was surprised when she noticed the lack of it here.

And when it comes to family, Ueura is alone here. None of her family is on this side of the world. She says she would go and see them, but money is always an issue. Plane ticket prices are soaring as high as the planes themselves, so she said she would have to wait to see them.

That's Not How We Say Hello

Naji Alanaz, a man from the capital city of Saudi Arabia, Riyadh, said he was surprised at the hidden culture not taught in English textbooks when learning to speak the language.

“When we were learning to say hello in English, I was taught just hello,” said Alanaz. “But here everyone says hello, how are you, and you have to respond with how you are.”

Alanaz said he doesn’t like this part of American greetings, as it adds needless conversation.

“You say how you are doing, but you're not really saying how you are doing. You just say fine or good and keep on going. At home (Saudi Arabia) we just say hello and go on from there.”

Alanaz also said it was a very annoying occurrence at first when arriving, as it was not what he expected and did not like how personal it made conversations feel from the start of them. “You have to make it up. If you don’t say it's fine, then you’ll be asked about it. That's why I feel nervous,” said Alanaz when talking about the start of a conversation.

Ueura even commented on the normal American greeting, agreeing with Alanaz that it was unexpected and annoying at times.

“Because ‘I'm good’ is like, okay, or (a) template. Even like (if) you are not good. I'm good. I have heard some American people go like, ‘Thanks, how are you? I'm good.’ I didn't ask you that. ‘So, how's your day? Like, it's fine.’ Yeah, right. We have to say that it's fine. Even though it's not. It doesn't make sense,” said Ueura.

Ueura and Alanaz said this typical greeting is strange to them because normally in their respective cultures not only are greetings very short, but also don’t ask questions about another person as that is something only asked when personally knowing someone.

“If someone said, it's boring, or something. I feel like, should (I) ask deeper? Or leave him alone? (What) should I do? Because you (have) not established that relationship yet? So you're like well, now what should I do,” said Ueura.

What's for dinner

It has become a staple of life for many, and even the go-to way to cook most foods for many: an air fryer. Beloved for its easy oven-like nature that doesn’t require lots of time to pre-heat.

Ueura said she had never seen one until coming to America.

“I never seen the air fryer or a big oven like that, because we have microwaves that have all those functions. Because our house is tiny. They don't have a big one,” said Ueura when asked about differences in cooking.

Japanese Microwave Oven. In Japan, housing is much more compact than in the U.S., so large ovens are seen as a luxury. To limit space needed in the house, this appliance can microwave, bake and toast food.

She also said that kitchen pantries were not very typical in Japanese households as they didn’t tend to stock up on food like Americans. “We use much more vegetables, fresh vegetables. Eggplants, potatoes, onions.” Most dishes in Japan are served with either mostly sides of vegetables or they are the main dish.

She even spoke about how American Japanese restaurants here were nothing like restaurants in Japan. “The first time I went to a Japanese steak house here, the Hibachi, I was like this isn’t Japanese. Yes, some of the foods are similar like the rice and noodles, but this isn’t traditional Japanese. It’s Americanized Japanese food.”

Alanaz said restaurants in Saudi Arabia had two sections to them. One for the single men, and another for families and women with their escorts. This was typical for his culture, as women didn't leave the house by themselves, and were usually accompanied by their husbands.

At the Potluck

Over Marshall Universities Spring break, Ueura held a potluck and invited friends of other nationalities to join her. Although it turned out to be a small gathering, she made traditional foods from Japan for those who attended to taste and enrich themselves in another culture.

She made okonomiyaki (Japanese pancake), which has a deceiving name, as it is not as sweet as the name may suggest. The bottom is made of a pancake, and topped with meats, cheeses, vegetables and sauce of the creator's choice, similar to the process of making a pizza. Ueuras was topped with teriyaki sauce, pork shavings, seaweed and cabbage.

Ueuras homemade okonomiyaki

Alongside this, she also made rice balls with salmon (and brought Japanese flavor packs for them), and a dessert called warabi mochi. warabi mochi, is a chilled dessert made of soy, with a chewy yet jelly-like texture, that has an added sweetener on top.

Rice balls made by Ueura, wrapped in plastic for individual servings.

Optional flavoring for the rice balls. A collection of spices and crunchy pieces. It came out of a "Peanuts" themed package, with some pieces looking like Snoopy.

Warabi mochi Ueura brought to the Potluck as a dessert. The brown powder on it is called kinako, made of roasted soybean powder. Although it adds sweetness, mochi is considered sweet enough to go without it sprinkled on.

A package of kinako.

Coffee and doughnuts, brought to the potluck by Alanaz as his nationalities dish. In Saudi Arabia, coffee is generally served with sweets, like doughnuts. The Arabian coffee Alanaz brought was not like traditional coffee in America. This coffee has spices much more present than other coffees. Alanaz said when your cup is empty, you shake it to show the server it is empty, and when finished and no longer want more, it is "checked," to show you do not want more. This is done by placing the cup on the table when the server brings the pot around.

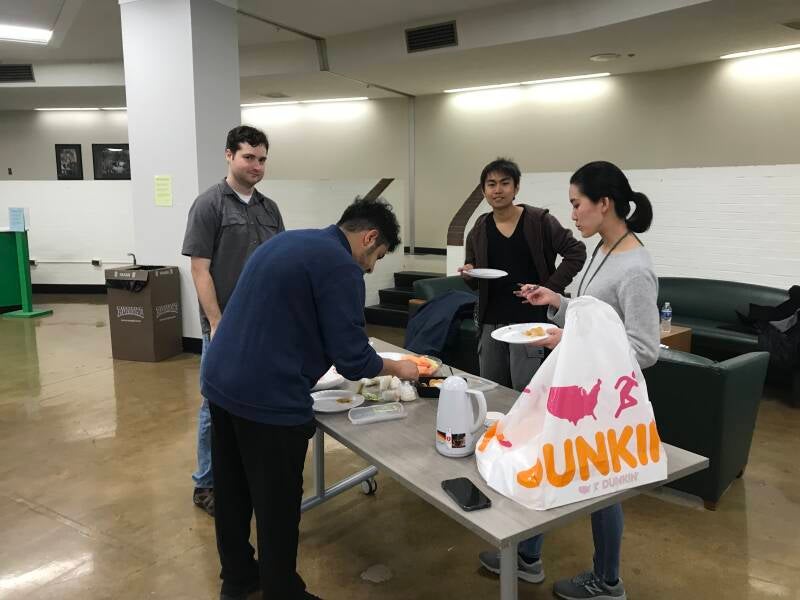

The attendees of the potluck. L-R: Chasse Stuart, Naji Alanaz, Yuto Masumitsu, Moeka Ueura. Masumitsu was from Tokyo, Japan, and had only been in the U.S. a couple months.

Holidays and Religions

During the winter break at Marshall, the campus empties out and very few students remain. One of those students was Ueura, who said travel costs were a barrier, keeping her from traveling home. Although she would have liked to see her family, she said the sights of an American Christmas kept her spirits up and gave her a reason to be excited. And, as a Christian, she had celebrated the holiday before, but not in a country that nationally celebrated it.

Unlike Ueura, Alanaz said he had gone home over the break.

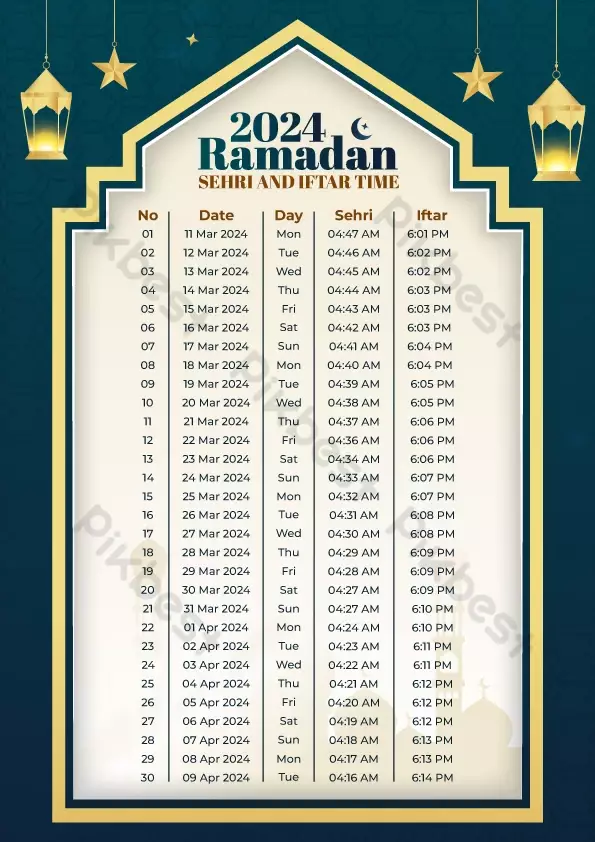

Alanaz, being Muslim, was observing Ramadan, the ninth month in the Islamic calendar, and is a month of fasting and prayer. Alanaz said that during the day, Muslims observing Ramadan are to not eat or drink during the daytime, and pray five times per day. When waking up, after breakfast, lunch, dinner, and bedtime. Alanaz was able to eat and drink during the day due to his diabetes. He said he still prayed, but that he had to eat and break his fast, but it was not looked down upon due to his condition. He did have to pass on Ueuras okonomiyaki, which had pork on it. In the Islamic religion, it is forbidden to eat pork, as it is seen as an unclean animal.

The 2024 Ramadan Calendar. 2024's Ramadan is 30 days, from March 11th- April 9th. Sehri is the meal eaten before sunrise, and iftar is the meal eaten after sundown. The calendar shows when the cutoff point for sehri is, and when iftar is able to be eaten each day.

Alanaz explaining what Ramadan is.

Add comment

Comments